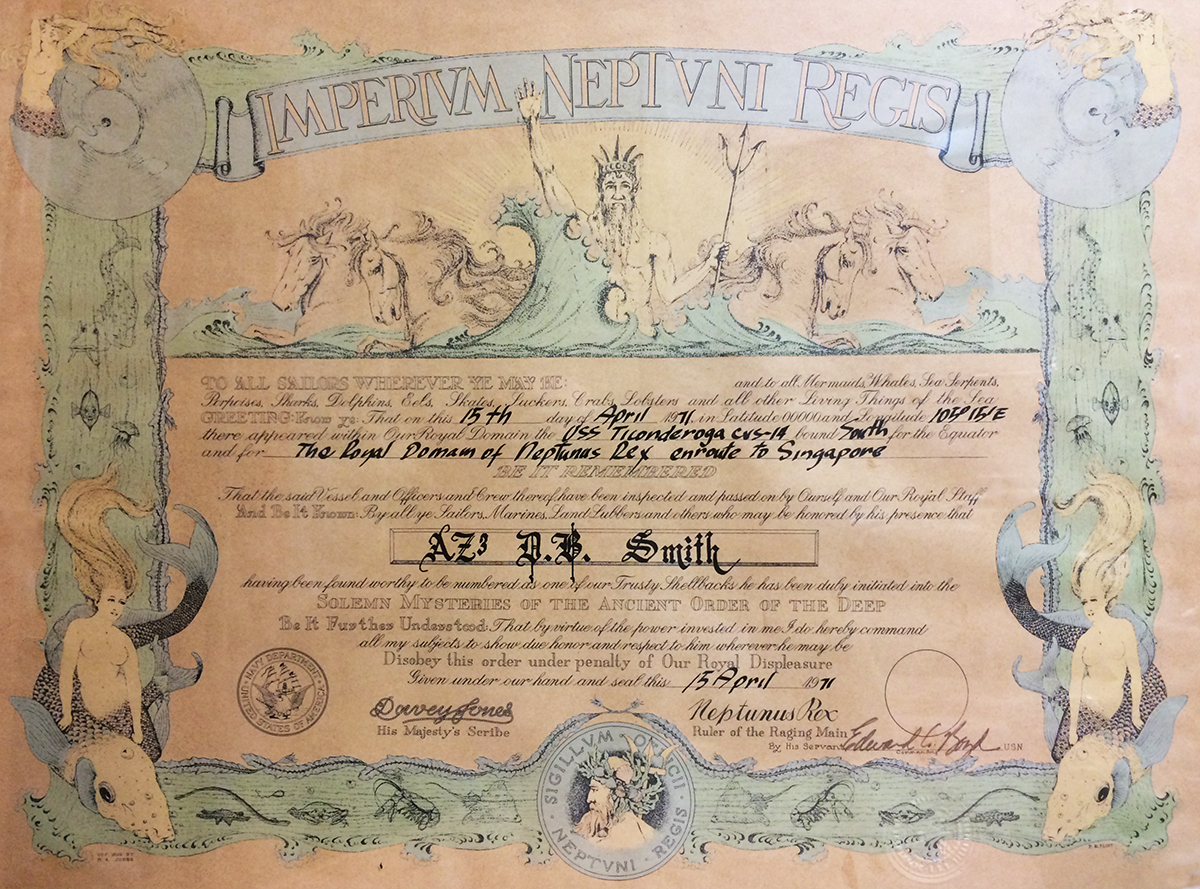

Published in the 2019 edition of Ageless Authors Anthology. This memoir is about fulfilling the trust a broken veteran put in me, and how I needed to trust someone as well. The photo is of a certificate I received after undergoing the Order of Neptune ritual while crossing the equator between Singapore and the Sunda Strait aboard the USS Ticonderoga (CVS-14).

“Welcome back,” I said.

His eyes reddened, and he gave me a strained smile. “Thanks, I guess.”

A decade after Mike came home from Vietnam, I hosted an end of the school year party at my apartment just off campus. He showed up as a friend of a friend. At a gathering where almost everyone was a stranger to him, Mike perused my densely decorated walls while drinking beer after beer. Amid the drawings, paintings, posters, kitsch, and objets d’art, he found an ornately illustrated certificate displaying “IMPERIVM NEPTVNI REGIS” in a banner across the top. The calligraphy below revealed that I was an initiate into the “Solemn Mysteries of the Ancient Order of the Deep.”

Of all the people who had been in that apartment, he was the only one who ever read and understood what that odd document meant. Moments later he interrupted my conversation, asking, “Are you a Shellback?”

As required by tradition, I answered, “You bet your sweet ass I am.” Then, “Are you?”

“I am but a slimy Pollywog,” he said with a wan smile.

Delighted by this rendition of an old ritual, I excused myself from my friends and asked him to join me on the landing.

Mike was a wiry, mid-sized, white guy a few years my senior. His shaggy blond hair set off his dark, troubled eyes. As we walked outside, his body moved in an odd manner that evoked the body pain of an old man. Tension played across his face as he tried to lean casually against the rail.

He inquired about my duty stations. Hearing that they included Da Nang Air Base in Vietnam, he visibly relaxed. I asked about his time in the service. He said that his first tour was as a Marine. Quang Tri, which I recognized as bad news. No word about a subsequent tour of duty.

After about five minutes of where-have-you-been and other inconsequential topics, the woman who brought him joined us. She and I weren’t close, but we had shared a few drawing and art history classes. Her behavior seemed to signal concern about Mike. As they left, I shook his hand, slightly squeezing his shoulder with my other.

“Welcome back,” I said.

His eyes reddened and he gave me a strained smile. “Thanks, I guess.”

Later that evening, my next-door neighbor, Robert, came home and joined the party. As I poured he and his girlfriend some wine, I mentioned that a guy who had been at the party earlier pegged me as a veteran. Looking at the prosthetic hook extending from his right sleeve, I said, “You can’t hide it like me.”

A strange look crossed his face. For a split second, I feared I had crossed a line in our friendship. His lips twitched, almost imperceptibly, before forming a tight grin.

“Don’t want to,” he replied.

As with most veterans of the Vietnam War or any war, I didn’t personally engage the enemy. My time in-country usually consisted of long days of doing my part to make a squadron function, sometimes followed by rocket attacks after 10 pm. Not much sleep on those nights, but most weren’t lethal. Over many months I experienced just a few minutes of danger. My unit would have faced almost no peril had we not shared a defensive ring along the western edge of the air base with an intelligence gathering squadron. VQ-1 was an important target.

Unfortunately, about twenty percent of American forces went through real horror. My neighbor Robert, drafted into the Army, earned his hook a few months into his tour. In high school, he was that handsome, popular athlete, excelling in football and track. He confessed that as a young black man, it was the only way he pictured success.

Now he neared completion of his masters in psychology. He wanted to work with veterans, emulating those who helped him take the journey from anger and bitterness to a man on a mission to help others. He knew it was corny, but he said their compassion was a gift he felt compelled to return.

Robert leaned close to me so even his girlfriend couldn’t hear. “If you need to talk…,” he whispered.

I surveyed the festivities, my bright, talented friends, and the signs of a nascent career. “I’m OK,” I replied.

The following Sunday afternoon I returned home to find my stressed party guest, Mike, sitting at the top of the 25 steps leading up to the landing Robert and I shared. His face was so red, I imagined his head as a cartoonish bundle of TNT, fuse burning. After taking a deep breath, I ascended the worn, wooden stairway.

Tears traced down his cheeks into blond stubble. As I approached, he looked down and away from me. I sat near him in silence. After a while he tried to speak, erupting in a single, explosive sob. He gathered himself and began again, telling me the story of his second tour, not with the Marine Corps, but with some sort of covert operations unit.

He told me how his small team would be dropped deep into enemy territory; how fantastic odds always doubted their return. Then there was the time they didn’t. That was when he said his nightmare of nightmares began, an ordeal he had kept to himself since his debriefing in 1969. Not a word in ten years.

I thought of all the secrets veterans were keeping. I had been off active duty for almost eight years, honorably discharged for just over five. Even those I knew to be veterans—those I had served with, went to college with, and shared many conversations with—rarely brought up their experiences. Silence had become our armor, our carapaces, in a new kind of conflict.

In those days, most of my university peers opposed the war, a stance in itself justifiable. However, their almost blanket condemnation of anyone associated with the war kept vets that needed assistance under the radar of those that could help.

Nevertheless, I believed that, despite some less than honorable behavior, most of those who actively opposed the war were honest patriots serving what they thought was a just and noble cause. I was equally sure of one other thing: those who chose to serve in the armed forces dared mortal risk to protect essential freedoms for fellow Americans as well as allies.

In World War II, despite some less than honorable behavior, that commitment served the just and noble cause of fighting alongside the citizens of France, China, Belgium, England, and the Philippines. Many of my generation, the sons and daughters of those heroes, applied that same ethos to the people of South Vietnam.

Mike believed this to the extent that he joined the Marines as an infantryman. In so doing, he took more of a risk to lose life or limb than I, a Navy airman. I respected that just as I did my combat Marine father who insisted his artistic son not enlist as a leatherneck.

On the stairs, Mike’s story began to burst out chaotic as a lightning storm, disordered and punctuated with cries and angry justifications. Buffeted by the emotional assault, I tried to hold my own on the pitching deck of his terrible tale.

As best I could, I pulled together this narrative:

A squad of either Viet Cong or North Vietnamese regulars captured Mike and two members of his unit. That night they marched through the jungle with the Americans’ arms bound behind their backs. At dawn, the prisoners dug pits, their jail cells. After being coerced into these holes, they were kept folded up in them during the day, covered with fetid forest trash. The next night they trekked farther, forced again at dawn to hollow out small dungeons. One American, wounded during capture, was too weak to dig. The soldiers dragged him a few yards into the bush. Hearing the fatal shot, Mike and his companion agreed that they had to make a run for it.

Before marching again that night, the jailers offered their prey a little rice. With a bit of energy, the pair tried to escape at what they thought was an opportune moment. They were recaptured but, by injuring one of their captors, angered them all. The next morning, Mike and his partner learned there would be only one pit.

Mike seemed to collapse inside. Almost liquid, he slid down a few steps on the stairs. He then looked up into my eyes as if begging forgiveness.

In an attempt at solace, I moved to his side and put my arm around his shoulders. He murmured that the next day he was able to elude his captors and eventually make his way to an American unit.

I jumped as he suddenly screamed: “Just a day!”

“It’s OK,” I said. “It’s all right, now.”

“No!” he hissed, “They made me kill Jimmy!”

All the air left my lungs.

I was horrified at what he said he had done, but I felt more than that. Something selfish. Mike’s turmoil stirred a guilt in my gut: how small a price I paid in this war while knowing so many suffered so terribly.

Fighting my dismay, I noticed my neighbor Robert’s Riviera parked next to my minibus.

“Mike,” I said, “There’s a guy here. Combat experience. He knows, man. He can help.”

Mike blubbered something about the secrecy of his missions. I tried to assure him that Robert wasn’t the government, that he would know what to do. He shook his head no.

For whatever reason, he had trusted me with his pain. I hoped he could do it again. I stood and eased toward my neighbor’s door. Robert answered my knock shirtless, no prosthetic. For the first time, I saw his abdominal scars.

“Got a Marine with severe problems here,” I said.

“Where?” he asked.

We looked around and saw Mike at the bottom of the stairs, ducking under the clothesline and heading for the front of our fourplex.

Robert shouted, “Marine!” Mike stopped, looked up at us, but immediately started to turn away.

“Marine!” Robert yelled again, pointing the stub of his forearm at him.

This time he stopped. Robert and I bounded down the stairs. By the time we got to him, Mike had dropped to his hands and knees.

Robert gave me a sign to stay back as he knelt in front of Mike.

Without looking up, Mike said, “I’m a mess.”

“Ain’t we all,” Robert replied, extending his arms.

Mike grabbed onto Robert, staring at the void where a hand used to be. He mumbled something I couldn’t catch. Robert nodded and gently pulled him to his feet.

Having gained a grain of trust, he led Mike back up the stairs and into his apartment. I went to mine and tried to process Mike’s appalling tale and the many questions it left unanswered.

Over the next few weeks, I checked on Mike through Robert. His consistent response was: “He’ll be all right.”

I understood his discretion but was worried.

Finally, Robert stopped answering my questions. He looked at me with concern. “You need to talk?”

“Me? No. I’m good,” I replied.

“Yeah. OK,” Robert said.

A month or so later, a musician friend known as Birdman showed up at my door. He wanted to see Francis Ford Coppola’s new release, Apocalypse Now. I told him I avoided movies like that. He asked: “Why?”

“I don’t know. Vietnam,” I said, surprising myself by mentioning it.

Birdman grabbed onto the revelation immediately. “You were in Vietnam? You could tell me how accurate the movie is!”

I resisted, but Birdman, possessing a nurtured joy and enthusiasm, was hard to refuse. I agreed to go.

The film caught the craziness of the war in Vietnam, I suppose, but it was the jarring similarities to Mike’s horrific account that left me emotionally overwhelmed.

Back at my place, Birdman wanted to hear about my wartime experiences. At first, I rattled off the funny stuff that happened, the sort of stories I told my family. Eventually, I related a very intense conversation I had with my new roommate when I arrived at my first duty station in Japan. That dramatic exchange only lasted a few minutes before he left on a mission and disappeared into the South China Sea.

Talking stirred my memory. I spoke of rocket attacks at Da Nang Airbase; about how one very close impact shook our barracks and lit it up in a dust-filled, yellow glow that illuminated my squadron mates scrambling like roaches for the bunker.

I told him how one day we were startled by an explosion and watched an inky smoke ball billow into the air. A VQ-1 Super Constellation had crashed at the south end of the Da Nang runway, killing 23 of the 28 people aboard. The men of my squadron shared lawn chairs and benches with the men of that squadron as we projected 16-millimeter movies against a sheet on the side of our communal latrine.

Going into the general horror of the environment, I recalled the ominous presence of black flies and razor-edged concertina wire everywhere. I related how all-too-often I saw young Vietnamese men with missing limbs trying to get around sandy streets on crutches and in wheelchairs. I recounted the appalling sight of aluminum caskets containing human remains stacked like any cargo outside the 15th Aerial Port terminal awaiting transport back to the States, and how we became inured to the stifling smells of the nearby mortuary and Agent Orange dump.

I also remembered the warm heartache of collecting and delivering supplies to orphans struggling to go on without their families.

Somewhat more cryptic, I tried to impress on him that it wasn’t just munitions creating casualties; there was always looming danger to fragile human bodies working with and amid giant machines of war.

Long after midnight, Birdman said goodbye, but I did not stop remembering. I put Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon on the stereo and set the turntable to repeat.

Dawn passed, and then noon.

When my neighbor Robert came home that evening, I met him at the top of the stairs and sputtered some sort of greeting

He looked tired but invited me inside.

Passing through the kitchen, he grabbed us each a beer. After he plopped down in his favorite chair, I landed on the couch.

“Talk now?” he asked.

Flushed with embarrassment, I stammered. After admitting I was freaked out, I contradicted myself. “Nah, I’m fine.”

Robert took a sip of his beer. With a slight smile he said, “Well, you look like hell.”

My mind raced through a thousand images and phrases, so every attempt to say something, anything, came up short of actually forming a sentence.

As if he could see my scrambled thoughts, Robert said, “Tell me one thing. Tell me about just one thing that’s on your mind.”

My tongue and brain seemed knotted together.

Finally, I said, “When I look at you, and what you went through. And what Mike…. I’m such a wuss.”

“Why?”

“My little troubles, they’re so…. They don’t compare. I’m…. I don’t know what’s wrong with me!”

Robert leaned forward. “Talk about the thing that won’t let you go.”

Tears filled my eyes, making me feel even more ashamed.

Softer this time, he asked, “What is that one thing?”

I spilled it. I divulged to Robert what I hid from Birdman, what I hid from everyone, what I tried to hide from myself. I told him about Killer.

I was aboard the aircraft carrier, USS Ticonderoga, on my second trip to the Far East. Killer was an aviation electrician in my division. After working the night shift, his life ended abruptly on an otherwise beautiful day afloat Subic Bay in the Philippines. A ten-ton hatch crushed him as he tried to close it in an attempt to dampen the clamor of a giant warship preparing to sail.

Now a petty officer, I was directing a crew taking aboard supplies for our division on the other side of the hangar deck when I heard a thunderous boom. For a strange, suspended moment, the massive steel against steel impact stopped all other noises and activity. Turning toward the sound’s source, I saw that the big hatch on the port side of the deck was now closed.

Someone could be hurt. After raising both hands to signal the crane operator to wait, I sprinted to and dropped down an identical hatch on the starboard side of the ship. Followed by a couple of the airmen in my detail, I raced abeam, past our electronics shops, toward the area served by the closed hatch.

Turning the last corner, I slid to a stop. Killer’s crumpled, almost headless body lay at the base of a ladder dripping with his blood and brains. Like an honor guard in shock, a few of the men that shared his sleeping quarters stood nearby.

His best friend, kneeling in the red mess, turned his horrified face up towards the new arrivals. Seeing me, he cried out: “Just four days!”

That anguished voice, ringing through a steel corridor splattered with the remains of our friend and shipmate, still haunts me. The thing was, he knew that I knew only four days remained in Killer’s six-year hitch.

Just four days before he would go home, leaving this dangerous military world behind him.

Just. Four. Damn. Days.

At the end of this telling, I felt played out, a fire turned to ashes.

Robert nodded his head as we sat in silence for half a minute or so.

“And you think that’s nothing?” he asked.

At first I was shocked. I couldn’t understand why someone who had been through what he had been through would think what I experienced was anything.

Yet, the way he questioned my attitude—so matter-of-fact—helped me see that because I had discounted my horror at losing a comrade in such a gruesome manner for so long, I was making myself unable to believe my feelings mattered.

I sat stunned, wondering why.

Curiously, I began to chuckle at my foolish reluctance to accept the truth of my history.

A pained but generous smile unfurled like a mainsail across Robert’s face. And there, right there in his compassionate features, he revealed what I needed to understand. In his deep, dark face, I saw a panoramic map of the rough seas and fair winds that comprise the length and breadth of the human voyage.

That startling vision caused a hatch to fly open somewhere deep inside me and I exploded in laughter and tears.

Robert, my blessed shaman, joined right in on my mournful celebration of realization. Pounding his hand on his knee and stomping his feet, he wept and laughed with me; just as he wept and laughed with himself, and with Mike, and with all war-burdened people seeking to navigate their hard-earned and solemn mysteries.

2 thoughts on “Solemn Mysteries”

Comments are closed.