In this memoir, I recount the tumultuous end of my tour of active duty in the Navy and the conflict of emotions that can accompany a significant transition in one’s life.

My friend, Petty Officer Third Class Doug Honspberger, took the photo on the left as we went ashore at Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan.

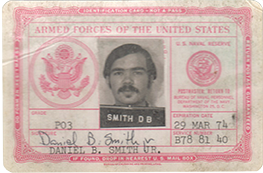

A newly issued pink military ID rested safely in the chest pocket of my dress white uniform, my seabag sat packed at my feet, and my heart ached for freedom.

Looking out my workspace porthole in the U.S.S. Ticonderoga as she steamed into San Diego Harbor, I saw North Island pier come into view as we rounded the channel’s bend. Although still bathed in the peachy light of a southern California dawn, it was jam-packed with my shipmate’s loved ones, who cheered and waved welcome signs as we drew near.

Along with about 2,500 sailors, airmen, and marines aboard this World War Two-era aircraft carrier, I was completing a 28,000-mile voyage, my second tour of duty in the Far East. In almost five months of 1971, we traversed the North Pacific Ocean and the Philippine, Java, South China, and East China Seas. We also made significant forays into the Indian Ocean and the Bering Sea, all on a mission to track and harass Russian submarines.

But now, finally, the fathers, husbands, sons, and brothers of those people on the pier would soon join them and go on leave.

No going on leave for me; I was headed home for good.

Although my active duty stint would end when our gangplank hit that dock, I wouldn’t get discharged. I still owed over two more years to the Naval Air Force Reserve.

That’s what the pink ID card was about. It replaced the green ID card of a serviceman on active duty.

Pink or green, military ID cards are critical to a serviceman’s ability to go on and off bases and ships. After forgetting my wallet in a grocery store near Atsugi Naval Air Station in Japan, I experienced the harshness of this requirement.

Getting hassled and detained for that sort of thing was just one of the many ways a regimented system dumps indignities on its personnel. It didn’t matter if you were an officer or an enlisted man; the Uniform Military Code of Justice (UMCJ) fell on you if you ran afoul of one of its many rules.

I sometimes thought it possible a long-forgotten planner tweaked the UMCJ for maximum irritation.

Everybody endlessly complained about it and, really, everything. All the more so for those intending to serve only one hitch. Not that the Navy cared. As one of my Chiefs told me: “A bitching sailor is a happy sailor.”

Those few free moments not consumed by useless carping were spent imagining idyllic civilian life. After years of griping and dreaming, the end of one’s enlistment would draw near. Then, the one-hitcher entered a state of time, space, and mind called “being short.” It was a psychologically fragile interval when the short-timer wound a little tighter and tighter every day, hoping nothing would go wrong.

Ah, but their joyful faces when the waiting was over!

That was my face until a commotion in the shop pulled me from my porthole reverie.

The uproar was a posse of master-at-arms (M.A.A.s) wearing sidearms, swarming through the shop, and taking ID cards from a few men in my division. I knew one of them, but he was curt when they came for me.

As ordered, I handed them my card while my immediate boss, Chief Roney, loudly demanded an explanation.

“It’s an investigation,” was the terse response.

Suffering this gut punch of dashed hopes, I felt like I was slipping into shock. Still, I was aware enough to see that most of the guys in my unit were trying to console the detained while a few raged at the M.A.A.s.

I felt such fondness for these men at this moment. Witnessing their concern and aggressiveness demonstrated the affection and loyalty a bonded military unit exhibits when their brothers are under threat.

Of all the detainees, the guys in our division sympathized most with the short-timer. That was me. They knew the anticipation of slow-coming freedom was hard enough without some ominous twist of fate.

We suspected that this mysterious occurrence was just such a convolution.

The M.A.A.s vacated our shop as the gangplank swung to the pier. The other detainees and I wished our shipmates a pleasant leave, and I said my last goodbyes to close friends as they left to join their loved ones.

Among the hardest to part with was Chief Roney. He had become like a father to me.

Although I was trying to hide it, he felt my turmoil. He even volunteered to stay aboard with me. Bless him, but his wife and daughter, who I knew almost intimately from his stories, were on the pier. There was no question about where the Chief needed to be. I thanked him and wished him and his family well.

Soon, almost everyone was ashore while I sat stunned, silent, and stewing with my fellow suspects Dilley, Conley, Murphy, O’Neil, and Stone.

At this moment, of course, my subconscious dredged up and started dwelling on the tragic memory of another short-timer.

Killer was an aviation electrician in my department crushed by a ten-ton hatch while we were docked in the Philippines a mere six weeks before. At the time of the accident, he only had four days left before the end of a six-year tour of duty. His story * summed up any short-timer’s greatest fear.

The M.A.A.s returned about an hour later and rounded up me, the guys in my division, and some squadron men. They led us ashore and marched us across the base to a small, single-story building.

Once inside, we were ushered one at a time into a stuffy interrogation room. Before and after questioning, we were kept separated and silent.

When it was my turn, I sat at a table in the small room with two men wearing civilian clothes and the practiced icy demeanor of professional lawmen.

One of them stood. Thin and sallow, he wore a black suit, white dress shirt, and black and red striped tie. I thought it was crazy to dress like that in this muggy chamber.

A chunky, southern sheriff-looking man with a ruddy face sat across the table from me. He wore a sensible, open-collared, short-sleeved shirt but was sweating more than his partner.

Only chunky guy spoke to me. He asked about my jobs and duty stations.

I told him about my time with a squadron before being transferred to the Ticonderoga and described my jobs in both assignments.

He then nodded towards a small, open, screw-top jar on the table. There was black goo inside with what looked like a popsicle stick embedded in it.

“Do you know what’s in the jar?” he asked.

Hong Kong had been one of our ports of call. Remembering the Opium Wars in China from high school history class, I guessed: “Opium?”

OK, I was more than a little naive and over a hundred years out of date. After news reports on the subject years later, I realized it must have been black tar heroin.

The investigator pressed on: “Do you have access to the utility space just forward of your shop?

I did not and told him so.

“Do you know ADR3 Neal?”

I replied that before we met again aboard the Ticonderoga, Neal and I spent a few months with VRC-50’s detachment at the Da Nang Airbase in Vietnam.

I also told them about the time we took refuge in the same sandy ditch near our hangar during a rocket attack **; how, as we hugged the ground, he cracked me up with exaggerated mock fear by screaming: “These buttons are too thick!”

However, I didn’t mention that we had smoked a joint minutes before that night’s attack, which may have made Neal’s antics seem more funny to me than they were.

When the investigators completed all the interviews, we unlucky few were marched back to the ship and ordered to stay on board until further notice.

At least we now knew the stir was about drugs of some sort and that it involved Neal. Although we didn’t like being dragged into his drama, we were also worried about him.

I considered the rest of my fellow suspects. We all worked near or walked by the utility space in question hundreds of times, and we all probably had some interaction with Neal, who had come aboard with a squadron. By that measure, though, everybody in the intermediate maintenance division and all the squadrons on board would be implicated.

I recognized but didn’t know the guys detained from the squadrons. Of those from my division, it appeared they chose Dilley, Murphy, and me because we looked hippy-ish. Conley and Stone were suspects because, like Neal, they were black men with Afros.

But O’Neil was a white, crew-cut lifer. He didn’t fit. So much so that the investigators in civvies assumed he was in charge of us. They didn’t interview him and had him march us back to the ship.

The rest of us knew the M.A.A.s took his ID card just as they had taken ours, but none of us pointed out their apparent mistake. It didn’t occur to us that he might have been the one who fingered us and that being detained was his cover.

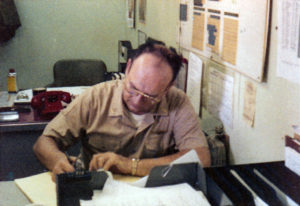

Once back aboard the Ticonderoga, all the detainees went off to forage for lunch or sit around and be pissed off. I chose the latter, going back to my desk and sitting there packed and ready to go for absolutely no reason.

Over the preceding three and a half years, I had seen how inconsistent and potentially ponderous military justice could be. Also, I knew no amount of wishing could produce a heroic troop of cavalry charging over the hill to rescue me from this nightmare.

Having nothing to do with the black goo, whatever it was, I was finding it easy to brew up some righteous anger. However, as a short-timer desperate to be free, I felt the walls closing in.

Unfairly accused and trapped by the system, my anger began to dissipate into the cold weight of helplessness.

Mercifully, before drowning in self-pity, I recalled the antics of my funny, system-defying friend Ferguson ***.

While having a muted chuckle about how he altered his name and demeanor to change how he was perceived, I remembered who I was and what I had learned about how the military works.

With that recollection, Ferguson became the white-hatted hero who rode into town to save the day. I now knew what I had to do.

But first, I needed to gin up the courage. For this, I called upon an exclamation I learned from John Schofield, my best friend on board.

Leaping from my chair, I yelled: “I’m a Third Class Petty Officer in the world’s largest nuclear navy!”

I grabbed my gear, stepped outside the shop, and shouted with everything I had into the cavernous, near-empty hangar deck: “I’m a veteran of a foreign war, and I don’t have to take this crap!”

Hoisting my seabag onto my shoulder, I strode to the M.A.A. office, neglecting to chant the rest of John’s increasingly profane exclamation.

Behind the counter, a bored seaman read a paperback while reclining to an impossible degree in a taped-up office chair. He looked up as I approached.

What little rank I had was easily visible to him in my dress white uniform. More to the point, he would immediately notice my service ribbons.

These brightly-hued pieces of cloth tell other members of the armed services where you’ve been and hint at what you’ve experienced. Having “color” on my chest when I reported to the ship earned me special treatment from the personnel office and a little extra respect from my shipmates.

Not wanting to give him time to think, I barked: “You’re supposed to give me my ID.”

“Uh,” he replied, not getting up. He looked just as confused as I hoped he would be.

I leaned over the counter and, like the interrogators had done to me, glared at him with stony, unforgiving eyes.

“S. M. I. T. H., Daniel B,” I said.

“Ah, OK,” he said, rising.

He looked around, thought about it, and unlocked a steel cabinet. After nosing around, he opened a small wooden box with index cards inside. A little shuffling through its contents produced my precious pink ID card.

“This you?” he asked, placing it facing towards me on the counter.

Feeling wildly over-caffeinated, I replied as calmly as I could muster: “Yes, thank you.”

I wanted to run, get off the ship, and leave the base before someone realized I was officially in custody. However, I was able to slide the ID off the counter and into my chest pocket with casual indifference.

Proud of my ruse, but with a substantial knot in my gut, I left the M.A.A. office and made my way to the quarterdeck. With every step, I expected to be found out and thrown into the brig.

Approaching the Officer of the Deck, I saluted him as required and requested permission to leave the ship. He inspected my ID and returned the salute.

Bless his lack of curiosity; he didn’t ask why I was going ashore so long after everyone else.

Having passed a formidable gauntlet, I saluted the ensign, traversed the gangplank, and strode down the pier to a launch that took me across the bay. After a nervous wait, I took a bus downtown and grabbed a cab to the airport. I booked a plane home with all but my last few dollars and called my parents in Dallas.

While I waited for my flight, a pair of shore patrolmen passed through the terminal. Their presence seemed odd, and a bolt of fear raced through my body, causing me to hold my breath as they came near.

As they passed, one of them nodded at me. I managed to smile and return the subtle greeting.

After holding my breath as long as possible, I exhaled with a barely audible “Whew!”

My folks met me at Love Field around two or so in the morning. It was good to be home, but the specter of imminent arrest haunted me.

Almost three tense weeks later, I received a letter from Chief Roney. Along with two handwritten pages, it contained my final active-duty paycheck that I had left in my desk’s top drawer in the stress of the moment.

Naturally, the Chief ribbed me about being so wealthy that I could afford to walk off without it.

He also filled me in on the convolution. He said there had been static from the investigators about my disappearance. But, he added that our department’s officers successfully argued that I must have misunderstood the directive to stay aboard the ship.

“I think they like you just because you worked hard and set a positive example for the younger men,” he wrote. “Maybe they had you confused with someone else. (haha!)”

After some news about his family and my closest shipmates, his letter ended with: “Have a nice life, Smitty. — your friend, Chief J.P. Roney.”

The Chief’s sign-off hit me like a 500 lb. bomb. As if looking into a mirror for the first time, I became aware of what I had experienced in the Navy, which had passed without examination while I lived it.

Tears filled my eyes as I stared dumbfounded at the letter, amazed that I could be such a blockhead.

The places I visited and lived! The fantastic, horrific, and awe-inspiring things I saw! The people I met, befriended, and served with!

So blinded by my fervent short-timer craving to get out, I hadn’t considered the inevitable torment of never again living a life so crazy, frustrating, and rewarding, and never again working and playing with my squadron mates and shipmates, my brothers in arms.

* Killer plays a part in Solemn Mysteries.

** Neal plays a part in Big Laughs in Rocket City.

*** Noms de Guerre is about Ferguson.