I have grown it, lived with it, loved it, and bid it farewell. This is a memoir about my head hair, body hair, facial hair, and, of course, vanity.

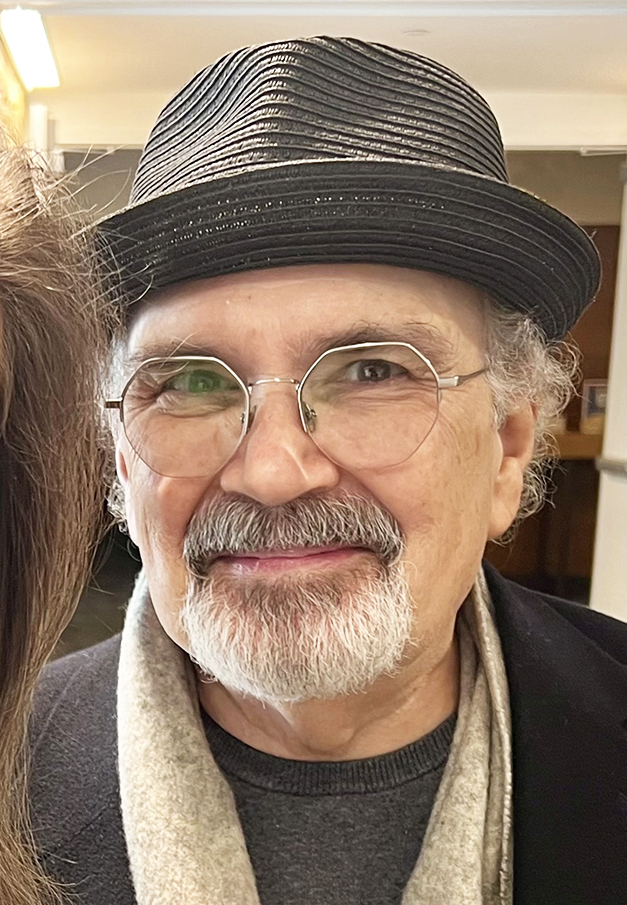

The photo is of the old lady in 2025.

I got chilled and couldn’t seem to get warm. Wrapping myself in a comforter was not doing the job.

“Don’t know why I’m so cold, I said.

“Because you’re an old lady!” said MB, the host of our gang’s Super Bowl watch party.

I’m a man, but I didn’t mind. She wasn’t wrong. MB knew medication suppressed my testosterone to an undetectable level that left me susceptible to hot flashes and chills. For lack of a better term, I was menopausal.

My wife added, “He lost his fur!”

Amy was right, too. The thick black and gray hair that recently covered my arms, chest, legs, and back, as well as my verdant armpits and crotch mop, had been reduced to a fine-stranded, sparse covering reminiscent of my body’s first months of puberty.

It felt like an attempt to erase my identity. Not an entirely unfamiliar feeling, given my fraught history with body bristles.

My father claimed he lost the hair on his head from wearing a steel helmet as a Marine fighting in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Well, maybe.

Dad was a muscular man with a friendly face and a story for everyone. Even if he stretched them a bit, those anecdotes were his way of sharing and bringing a smile and a story out of someone else. He made friends quickly and deeply.

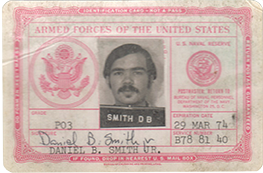

I acquired some of that skill from him. Also like him, I lost my hair, but due to inherited genes, not from wearing helmets in the tropics. At least, I don’t think so. I did share that sartorial turn with him during my shorter stint in the Vietnam War.

Another physical similarity: as the hair on my head beat a retreat from my forehead, my body hair continued to grow darker, denser, and more curly.

Well before that, though, my mustache hair grew thick, straight, and walrus-like. So much so that by the time I left high school, I was tired of the red, razor-burned upper lip that shaving caused. However, as I had to report to boot camp for the US Navy 15 days after graduation, I couldn’t immediately start cultivating a mustache.

After boot, though, I stopped torturing myself and grew a healthy “cowboy.” The look suited me and, as mustaches do, became my distinguishing feature.

Unfortunately, some people did not appreciate my choice of facial hair. OK by me, I would have been happy with it merely being tolerated or ignored. But, since a certain type of career Navy man just couldn’t leave it alone, I had to fight two battles to keep my mustache while on active duty.

The First Battle

Chief Combs was the Maintenance Chief and Senior Master Chief of the squadron in Atsugi, Japan, which was my first duty station. Although he looked me in the eye at five and a half feet, he was the most powerful enlisted man in the unit. Junior officers dare not cross him, and senior officers tread lightly. All enlisted personnel jumped to do his bidding when he issued an order.

I reported to the squadron with well-developed facial hair and initially received no static about it, maybe because the first guy I worked for had a lustrous “Zapata” mustache. Fabio Martinez, Marty, was a large Mexican man with sparkling intelligence who was well on his way to getting his US citizenship via a twenty-year stint.

Although a rated jet engine mechanic, Marty was the barracks Master-At-Arms. I had a great time on the cleaning crew there, but the powers that be soon called me to the hangar to work in my official rating of AZ (Aviation Administration).

That move put me under the aegis of Chief Blake, a lanky, bespectacled Hoosier with a wacky sense of humor. Unfortunately, like the chiefs running every section, Blake worked for Chief Combs.

The Maintenance Chief was old school. Every time he looked my way, his eyes were accusatory slits with a small fire inside each one, but he said nothing.

Over the next two and a half months, I learned how this squadron did aviation administration.

First, I worked in logbooks, where I learned about keeping accurate airplane logs that detailed the history and maintenance schedule of every mechanical part of the C-130s, C-1As, and C-2As that this squadron flew. Not just bookkeeping, I had to pester pilots, plane captains, and engineers for details about missing information.

Then, we touched on how to analyze the history of these parts, as well as the procedures in the shops that maintained them, to identify ways to improve both mechanical and human performance.

Finally, I worked the “hot seat,” the counter in the maintenance office where all incoming flight crews reported. It was the nexus between Squadron Operations and Aircraft Maintenance. A busy place.

In the hot seat, I worked with Operations to schedule and configure flights. I met every arriving crew and helped them fill out a “gripe sheet” of equipment problems, structural failures or stresses, and any other issues that may hinder the aircraft from performing at 100%. Then, I wrote work orders for each applicable shop or to Supply and followed up on each gripe by logging and reporting on the progress of these work orders.

After a couple of months, Chief Combs cornered me in the dark hall between the maintenance office and the logs and records office.

“Cut it,” he growled.

“What, Chief?” I asked.

“Your mustache. I want it gone.”

“Aye aye, Master Chief.” There was no other answer.

The next day, he nodded with approval when he saw my naked face.

The morning after that, I did not shave my upper lip.

Midday, Chief Combs cornered me in the dark hall again.

“Airman, you missed part of your face when you shaved this morning.”

“I must have,” I replied.

The Master Chief grinned just a little before saying, “I need you to volunteer for our detachment in Danang. As you know, Petty Officer George was supposed to go, but we don’t think he can handle it.”

He was referring to “Babbling George.” Unfortunately, the nickname accurately indicated his emotional and mental stability.

Combs continued, “While it’s technically a petty officer position, we all agree that you have what it takes. You’ll be in charge of logs and records, as well as sitting in the hot seat. You’ll send us a complete report every two or three days.”

Flattery and the lure of danger. Combs knew me better than I knew myself..

“Aye, Master Chief,” I said while nodding in assent.

Two weeks later, one of our C-130s corkscrewed into Danang Air Base and dropped me off at my new assignment. The squadron’s detachment provided support to aircraft carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Although I had less equipment and fewer airplanes to deal with, we launched and recovered far more flights per day. As you may imagine, operating in a war zone brought its own difficulties. Nevertheless, I did my job.

Almost six months later, on my 20th birthday, I boarded one of our C-2As and flew back to Japan from Vietnam.

I deplaned in front of the squadron hangars at Atsugi sporting a big mustache. Chief Combs greeted me with a handshake and didn’t say a word about it.

The Second Battle

Three months after my return from Danang, I went home on leave. Thirty days later, I reported to my second duty station on the USS Ticonderoga, a refitted World War II aircraft carrier docked in San Diego Bay.

After boarding the ship, I took a place in the “new guy” line with a bunch of recruits, apprentices, and other airmen, all in our dress blue uniforms. A clerk from the personnel office walked along the queue, checking us out.

“Got one with color, here!” he cried out.

He was referring to the campaign ribbons from Vietnam that adorned my chest.

He asked me for my full name and service number while scanning a roster.

“You’re a petty officer now,” he said while directing me to the head of the line.

I had time in grade and thought I had done well on the test three months prior, but as I was competing against all similar Airmen worldwide, I was surprised. Pleased, too, by the raise in status and pay.

The Personnel Department checked my name off lists, made log entries, and wielded rubber stamps before sending me to the Aircraft Intermediate Maintenance Department office.

Upon entering, the first thing I noticed was Felix the Cat images everywhere: on the face of a wall clock, on a homemade poster, on the handle of every phone, and oddly, on a call bell like the kind you’d find sitting on a deli counter.

It sat on the outside corner of a desk near the door. Airman Machowski, seated at the desk, greeted me and said I might as well drop my sea bag and sit a spell until they figured out what to do with me.

Of course, I was curious.

“Felix?” I asked.

Machowski’s conspiratorial smile told me all I needed to know.

“It’s our secret name for Lieutenant Commander (LCDR) Alexander, the department’s second in command.”

“A prick,” he added.

“We call the bell our Felix catcher. Alexander thinks it’s a morale booster because that’s what we told him. So, to show he’s one of the gang, he rings it whenever he leaves or comes into the office.”

“I can see how that would come in handy,” I said.

“It does!” Machowski said.

As if on cue, LCDR Alexander entered the room, but he did not ring the bell. Instead, he looked squarely at me.

“That’s not a regulation mustache,” he said.

“Oh, no,” I thought, “He IS a prick.”

“You’ll trim that to regulation, or you’ll shave it off by morning muster. Understand, Airman?”

“Sir,” Machowski said, “He’s just been promoted to Petty Officer Third Class.”

Alexander closed his eyes in frustration as Machowski grinned from ear to ear. I could see Machowski chose to skirmish with deniable petulance.

“You understand, Petty Officer?” Alexander asked me.

“Aye, Sir,” I replied, but I smoldered with resentment.

“Come with me, uh, Smith,” Alexander said.

I followed him into an office where I met the department head, LCDR James, a Gary Cooper type.

“This is Smith, the new AZ,” Mr. Alexander said. “I’ve already ordered him to correct his non-regulation mustache.”

Mr. James rolled his eyes. “Thank you, LCDR.”

Then to me, “Welcome aboard, Smith. I think you’ll be heading to IM2 Division, but check back here in the morning.”

Wachowski directed me to one of the department’s sleeping quarters. I found an unused bunk and locker and chatted with a few guys before going to sleep.

The next morning, I did a half-assed job of trimming up my mustache and reported to muster.

Mr. Alexander pounced on me immediately, getting right up in my face. He let me know beyond any shadow of a doubt that he was not pleased with the state of my mustache.

I already knew that the chain of command could be supportive, giving you direction for success, or it could be a drizzle of aggravating chicken shit. I was enraged that I had to cope with Mr. Alexander’s lack of insight, but I managed to hold it in.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to tread water for very long. Wachowski escorted me to the IM-2 Division while explaining that the LCDRs expected me to fill two billets: Air Maintenance Equipment Administrator and Division Yeoman.

He introduced me to Warrant Officer Duren, Chief Palmisano, and Chief Roney. Duren was the Division Officer, while Chiefs Palmisano and Roney were my direct bosses for each of the two jobs I held.

Mr. Duren was sweating more than the temperature called for, but he came across as genial if a little scatterbrained. Before I arrived, the men in the division painted his telephone red and labeled it “The Sweat Phone.” He not only took it in good humor, he was proud of it.

Over the next five months at sea, I rarely saw him. Every morning, he would grab a clipboard and some files and rush around the ship. He confided that since he perspired easily, he used it and appearing as if he was doing something important to get promotions.

Chief Palmisano was a tall, olive-skinned man of Italian and Cherokee lineage with an impressive hook nose. Everyone who worked for him or with him felt like they were a member of his boisterous family.

He ran the shop that maintained aircraft support equipment, all painted yellow for visibility. It included everything from a towering aircraft crash crane to spotting dollies, tow tractors, and forklifts, as well as sandblasters, jacks, air start units, and other specialized tools.

In total, I was responsible for maintaining logs and records on 99 pieces of “yellow gear,” tracking their usage, repair, and loan status to shipboard squadrons.

As far as my other job, I was technically the always-absent Mr. Duren’s yeoman. In reality, I worked for Chief Roney because he ran the division by default.

I was lucky. Chief Roney was warm, fair, and helpful. Plus, I learned how to drink a lot of strong, black coffee under his tutelage. He explained to me, with an impish smile, that it was important to wash one’s dark-stained coffee cup on the first day of every month for the sake of good hygiene.

A yeoman’s job is that of a secretary, except that I also assigned the men in our division to watch duty and work crews. I was careful to spread these chores evenly and to take a shade more watches than any of them.

I spent a few days getting to know the men in my division and becoming acclimated to life aboard a ship before LCDR James came to visit me.

He explained the dismal history IM-2 Division had reporting maintenance and operations data. The US Third Fleet gave it a score of 30 out of 100 – a deep F, and he was under a lot of pressure to improve the functionality of the division’s reporting procedures and remove the stain on his command. He hoped I could fix it by the last week of December when Third Fleet would conduct another detailed evaluation.

That gave me less than a month.

I had already noticed that it was difficult for division personnel to know what was happening with each piece of equipment at any one time. I also discovered that the maintenance logs of each piece of equipment were either sparse on details or missing entirely.

Since I didn’t have a model that fit this situation to replicate, I created a system that made sense to me using design skills I didn’t yet know I possessed.

First, I did the obvious thing and created a logbook for each piece of yellow gear. If there was no data in the log, I interviewed long-term members of the division and reconstructed a reasonable facsimile of the equipment’s history. While I was at it, I put on my yeoman hat and set to organizing and updating the division’s personnel, orders, and correspondence files.

Second, I built a giant board with horizontal slots that held cards containing identifying data and a historical summary for each piece of gear. As a card moved from left to right, it depicted the gear’s status in a way visible to the entire shop. It made it easier to assign and track repairs, as well as to see which squadron had it checked out on loan.

Throughout this period, I attempted to avoid Mr. Alexander, the notorious “Felix.” Nonetheless, he spotted me once and threatened me, which had the unintended effect of teaching my chiefs and crewmates to look out for me by deflecting him or hiding me when necessary. Being instantly likable like my father has always had its perks.

I worked hard, 14 or more hours a day for over three weeks. The project wasn’t complete when the inspectors came aboard, but I was ready.

They reviewed my files and asked me increasingly detailed questions about how my system worked. I had ready answers as well as clear justifications for everything.

After two full days of grilling, they departed. I was exhausted.

A week later, Mr. James came down to the little office that Mr. Duren, Chief Roney, and I shared and gazed out the porthole near my desk. He took a couple of puffs on a slim cigar as he squinted into the southern California sunlight.

Still looking out the porthole, he told me I had pushed our reporting score up into the 90s, a solid A, and that, of the entire department, the investigators were particularly impressed by what I was doing.

The LCDR turned to look at me and said: “Smitty, you don’t have to worry about Felix ever again.”

I was happy to hear that my work paid off, relieved that my antagonist was no longer a threat, and delighted that the department head knew the prick’s secret name.

By the end of our West Pacific tour, Mr. James had grown a mustache a lot like mine.

– – – – –

I realize that these two stories don’t describe battles in the traditional sense. I did not wield arms or employ physical strength in a mighty clash against an entrenched opposition. Nor did I protest or pout as some of my peers chose to do in the face of annoying regimentation. Using a more subtle approach to conflict, I proved my worth to my bosses by showing up for the job and working hard.

Demonstrating that I was indispensable bought me the freedom to be eccentric.

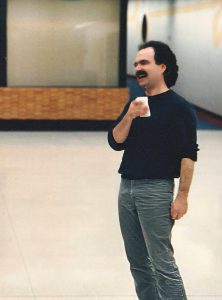

From that time on, sometimes with other configurations of facial hair, head hair, and a general bohemian bearing, I kept the caterpillar on my upper lip.

Mostly.

Every eight years, I voluntarily cut it off to prove to myself and my gobsmacked associates that I had a face.

One of these shavings coincided with the same action by my friend Lee Schloss, who also descended from, as they say, a small, hairy people.

On that day, freshly sans mustache, I answered a knock at my door only to be confronted by my similarly bare-faced friend. We stood motionless for a moment on either side of the threshold before both of us slowly raised our right hands and touched the other’s hairless and untanned upper lip.

We looked like a chimp seeing itself for the first time in a mirror.

Those occasional face shavings aside, I had a youthful and unjustifiable pride wrapped up in the virility implied by being a hairy guy.

When I was in my mid thirties, I ran into a pair of coworkers outside my studio. Helen, the office manager for the post-production company we worked for, was chatting with our receptionist.

As I walked by, she pointed at my left jawline.

“You missed a strip shaving this morning,” she said.

Appalled, I rubbed my hands all over my face, not calming down until I realized it was smooth.

Helen and the receptionist had a big laugh at the expense of my now-exposed and oh-so-fragile male ego. The red heat of embarrassment burned more inside than on my face and ears.

An experience like that should have cauterized my useless self regard. Nevertheless, I persisted in this peculiar self-absorption even as I left youth behind. That is, until a few years ago when ADT treatment for stage 4 prostate cancer sheared my fleece.

Although it made my body hair fall off, in an act of chemical solace, it left my formidable mustache in place: gray, proud, and still around.

Today, I wouldn’t flinch at Helen’s joke, just like I didn’t object when MB called me an old lady. Instead, I look back amused that I battled petty despots for an expression of personal identity that barely disguised my vanity.